We’re sharing a book club that was once hosted by now-author Will Willingham.

A few things have changed in Will’s life since he first led us in

reading Ordinary Genius. But poetry is not one of them…

I could have learned to play the violin when I was in fifth grade, but all the girls joining orchestra in my class wanted to play the violin. My brother and sister both played viola when they were in fifth grade and so, conveniently, my family already owned one. “I will play the viola, ” I said.

When I was in sixth grade, I could have switched from orchestra to band, and learned the clarinet. My family also owned one of those. All the girls in my class who were joining band wanted to play the clarinet or the flute. “I will keep playing the viola, ” I said.

My family moved out of state and I started eighth grade in a school without an orchestra. I joined the city’s adult symphony instead, sitting second of two chairs. I took private lessons from a man who looked to be a cross between Professor Snape and Harry Potter. None of the girls in my class wanted to take lessons from him. With his large round glasses and long, greasy black hair, the spindly music instructor frightened me only slightly less than his brutish, muscular wife who always answered the door red-faced and angry. “I am here to play viola, ” I said.

As a tenth grader, I moved to a city with neither an orchestra nor a private instructor, relieving me, I thought, of any further musical obligations. But then all the girls in my class convinced me to learn not the clarinet, but the string bass so I could play in the band. When parade season marched in I faced the conundrum of marching with an instrument taller and wider than myself. “It’s not as though I play the clarinet, ” I said.

The band director handed me a pair of cymbals and motioned me to the percussion section where I wasted no time in demonstrating a complete lack of rhythm. So he gave me a flag emblazoned with my school’s Bulldog mascot and a cheerleading skirt instead, sending me to the front of the formation. All the girls in my class wanted to wear a cheerleading skirt but I refused, preferring the Q-tip shaped furry hat and knock-knee-mystery covering of the regular marching uniform. The director suggested I just keep moving and try to look like I was in step. “I wish I played the harmonica, ” I said.

***

Some decades later, my sense of rhythm has not improved. When Kim Addonizio talks about folks who “can’t hear where the stressed syllable falls, ” she’s talking about me. Breaking down form poetry requires graph paper so I know which syllable is more stressed than I am. Even so, she seems to think that there’s merit in learning to write within the restrictive meter of the sonnet.

Writing a sonnet will teach you about economy, about structure, about how searching for a rhyme or following a rhythm can lead you into unexpected territory. …Don’t expect your first sonnets to be fabulous poetry. They may be silly, or corny, or clumsy, but you’ll begin to appreciate the challenges and possibilities.

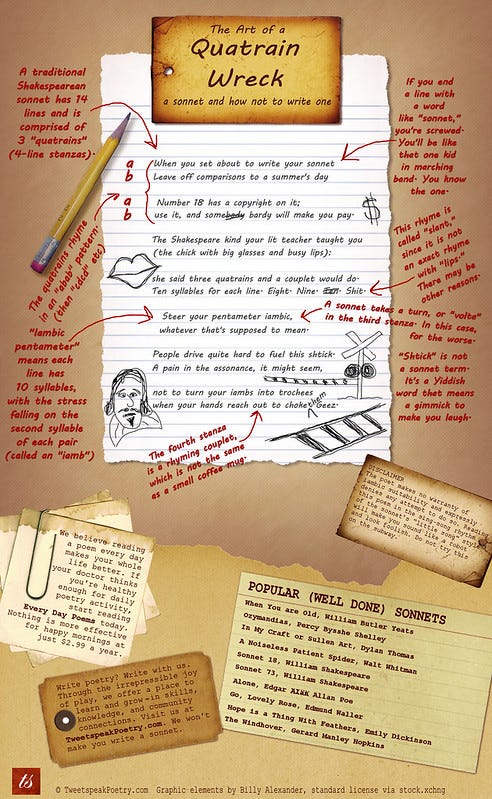

Though the sonnet can follow various patterns, Shakespeare’s style may be the best known: three quatrains (four-line stanzas) written in iambic pentameter (ten syllables, stress on the second in the pair) which rhyme in an alternating pattern, ending in a rhyming couplet, with a turn, or volta in the third stanza.

Easy peasy, lemon squeezy, right?

Not for me.

But Addonizio asked me to try, and said it might be bad and that’s okay, so I gave it a go.

If words had visual weight I’d see their stress

like boldface on the place where I should lean.

The rhythm hides itself in randomness

and writing with the meter makes me scream.

Who cooked this up I really want to know.

I cannot measure meter on this scale.

I’m blaming Shakespeare, yes, he made it so.

He wrote those numbered poems so I would fail.

I say: I do not like it, Sam iamb.

I will not write it with a troch. I will

not write, it makes me choke, and then enjamb

the blasted quatrains. They just make me ill.

The sonnet’s best left to professionals.

The rest of us can’t count our syllables.

“And now, I wonder if it’s time to learn the kazoo, ” I said.

____________________________

For tips on writing (or fighting) a sonnet, check out our Quatrain Wreck sonnet infographic. Even if it doesn’t help you write one, it might just make you laugh.

~

Now it’s your turn. Compose your own sonnet. Share it in the comments. We’d love to read!

Adjustments: A Novel by Will Willingham

Photo by Ms. Uppy, Creative Commons, via Unsplash. Post by Will Willingham.