This post is a reprint of L.L. Barkat’s The Hearing of the Sea: Thoughts on a Broken Thing,

that first ran at Tweetspeak Poetry and Englewood Review of Books.

While the piece is actually a book review, it’s also a reflection that gets you to consider:

what do line breaks mean in my poems?

That is a fun question to consider!

How do you handle line breaks in your poems?

What does a line break mean to you?

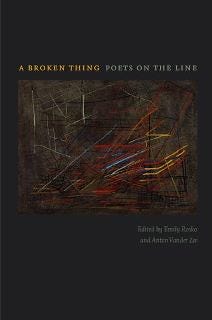

I am tempted to review A Broken Thing: Poets on the Line with a single line.

If I could do this, what line would I choose? Perhaps something from one of my recent stream-of-consciousness reflections…

Either of these lines would say it all for me. Or be only a beginning. Either line would stand alone, yet it would beg to stand together with more thoughts, poured out from the wider stream, or sea, if you will.

This is the dilemma, or perhaps the dynamic, that the poets in A Broken Thing have addressed, wittingly or unwittingly: finiteness and the infinite, singularity and plurality, isolation and community. A line stands alone. But no, a line stands together with other lines and the poem as a whole. A line is a piece of the shell. But no, a line is the whole shell and it echoes the sea in which it first found its life. A line is a bone, compact and hard and bounding, but no, it has absorbed an eternity of salt-water that will not be confined.

If I seem to be wandering in poetic thoughts, when I am supposed to be reviewing a book, then this is an accurate and important appraisal, because A Broken Thing will do just this: make you think, and think again, and argue with yourself, and agree with (and then argue with) more than seventy poets, on the issue of the line in poetry. Like the sea, with its constant movement, your thoughts will ebb, flow, crash, eat away at shores and build them; you will need more than a day, or even a month, for this reality.

When I come across a book as provocative as A Broken Thing, I know I will recommend it, but the question is… to whom, and in what context. In the case of this book, I find myself asking who has the mental stamina, the philosophical bent, and the luxury of time to read and appreciate something this dense, thoughtful, and poetic. Surely not a student, unless that student is allowed to take a long time to pore over the words. It would be pure malice to assign this as a required text with a vigorous reading schedule. In the interest of finishing on time, the student would constantly need to fight the invitation to stop and consider…

By brief moments… a life can appear

The line… is a rebel thing

The line is telling, not only in what it says but what it doesn’t say

Her line cuts me out

I do believe that a poem is the sum of its lines

embroiled in the problem of the line was the problem of deciding

We don’t have time for the line

I want the line-break to tell me…where a speaker butts up against silence*

And so it continues, until you feel your mind might implode with the myriad thoughts that agitate and generate, foil and unfold. From dividing political assertions (the line is “a gendered and fascist reliquary containing the careers of Pound, Eliot…”) to unifying one-world assertions (“this connection of everything with lines”), you will find that you cannot settle in one place. And while you might find some good advice on how to construct a more effective line, you will not necessarily feel you’ve made any decision on the effect or nature of a line.

“The line in digital poetry is not broken”; Stephanie Strickland begins her essay with this line, somehow oddly embodying the dynamic with which we began. She makes an assertion in one direction—wholeness; yet, visually, her assertion contains a contradiction. One cannot help but notice: the claim stands so lonely at the top of the page. Ultimately, her opening holds the finite and the infinite in tension. It suggests singularity and plurality, isolation and community, all at once, if that were possible.

I could continue sharing from Strickland’s essay or from the book as a whole. I could go on. There are more lines worth quoting, more thoughts worth turning over in the palm. Yet this issue of making decisions, to trust in the finite—a seemingly bounded set of words—to say what is beyond, suddenly confronts me. I am back to my initial temptation: shall I say what I need to say here in a single line?

If the shells still hear the sea though they are in pieces, a single line might do.

____

*Quotes, in order of appearance, are from the following essayists in A Broken Thing: Kazim Ali, Marianne Boruch, Cynthia Hogue, Christine Hume, John O. Espinoza, Gabriel Gudding, Ibid, Cynthia Hogue.

Tell Us in the Comments

• How do you handle line breaks in your poems?

• What does a line break mean to you?

Photo by Ashkan Forouzani, Creative Commons, via Unsplash.

Line division seems to be tricky for me -- I've dived back into writing poetry this year, and am naturally inclined to line break when I reach a natural pause in thought, or to allow an emphasis on a piece of language, to let it linger longer than a brief moment. But I also think it's fair to say that prose poetry has its own place within the genre even without the traditional line breaks we're used to seeing. Use of spacing is as artistic and intentional as it is functional.